The Orthodox Shoemaker

This story is told in my voice, but the shoemaker himself was very real. I first came across his tale in a book on Jewish life (I´m not Jewish, but this book landed on my hands), a brief mention of an Orthodox craftsman in Poltava who kept working on the day when everyone else insisted he shouldn’t.

That tiny fragment struck me like a well-aimed hammer, so I stitched it into a full first-person narrative. Consider this piece a polished boot inspired by a very real sole.

I am from Poltava. It is the late 1950s, a time when the government wanted everyone to look the same, think the same, believe nothing, and work quietly.

Religion wasn’t forbidden, exactly , just watched, discouraged, inspected.

Our neighborhood was one of those old corners of the city where traditions clung to the walls like winter frost. You could tell by the way people dressed on certain days, by the quiet greetings exchanged at dusk, by the baker who closed a little earlier on Fridays. No one said the word “religious”, you simply knew.

Families carried their customs like hidden embers, warm, but always at risk of being stepped on. Some tried to keep the old rhythms alive behind closed curtains. Others let them go, not out of lack of faith, but out of exhaustion. Or fear. Or simply because survival had its own rules.

And then there was me, the shoemaker.

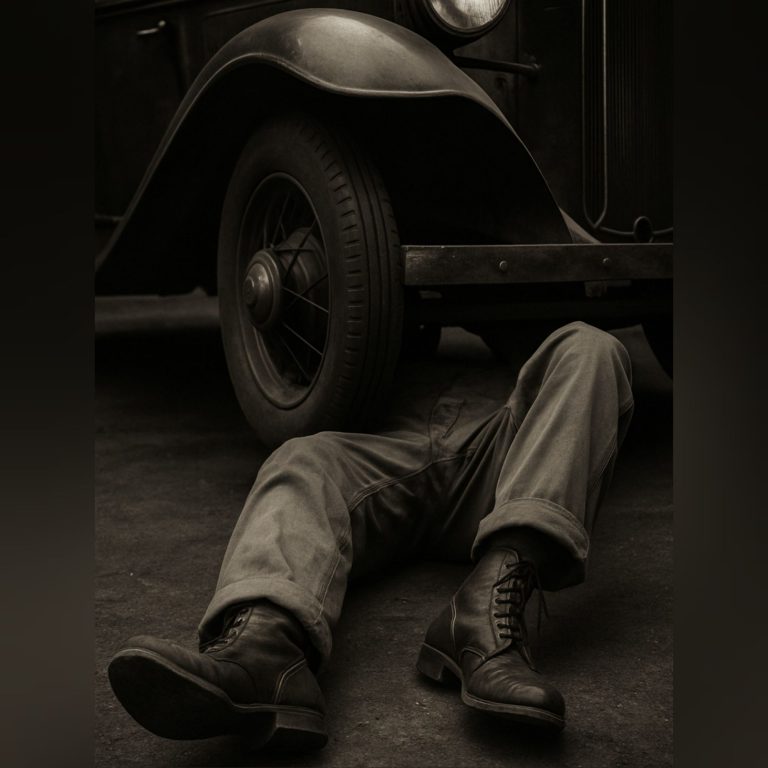

My workshop was small enough that the cold touched every corner, but big enough to keep me company. The streets outside were strict and watchful. But inside, the only authority was leather, thread, and the stubborn patience of my hands.

Every Saturday, the same thing happened.

People I knew, men who bought my boots, women who brought their children’s shoes for mending, neighbors who shared potatoes and news, walked past my window.

Some quickened their pace.

Some slowed down and glanced in, giving that look.

The one that didn’t need words to say:

“You’re working today? Today?”

They didn’t mention heritage or background out loud. They didn’t need to. In this neighborhood, everyone knew exactly who came from which families, and whose windows stayed dark or bright on certain nights.

While they walked to wherever they were supposed to be, I sat at my bench, stitching a welt, shaping a heel, warming the leather with the flame I wasn’t supposed to use on that day.

My hands were busy, yes.

But my mind? Not busy at all.

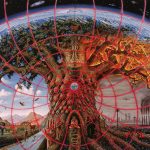

When I worked on Saturdays, I wasn’t breaking anything sacred. I was entering it.

Because something happened in that workshop that no committee, no neighbor, no rulebook could measure.

When the thread slid through the holes, it sounded like breathing.

When the hammer tapped the sole, it felt like a heartbeat.

When the leather softened, it stopped being leather and became something closer to truth.

Some men found freedom in stopping. I found it in creating.

Not because I wanted to rebel.

Not because I didn’t understand tradition.

But because the moment my hands began their quiet dance, something in me settled into place, like the world and I were finally in the same room.

My ancestors honored this day in their own way: quietly, stubbornly, with candles, songs, and stories whispered so softly they barely touched the air. I carried them with me, not in rituals, but in tools: the brass awl that had survived more borders than I ever would, the knot I tied the way my grandfather taught me, the silence I kept without meaning to.

People outside followed the rules.

Maybe they felt free.

Maybe they didn’t.

I don’t really know.

But inside my workshop, I had my own seventh day, not marked by calendars,not enforced by anyone, but found in the exact second a pair of boots stopped being pieces and became whole.

I would lift them to the light, let the dust swirl around them like snowflakes, and breathe out.

That breath.

That moment, was rest.

That was my freedom.

“Old Poltava”, www.artgalleryif.com